As of today, more than 1,378 children have fallen victims of Russia’s armed aggression. They are the generation of those who were born, grow up, and study to the sound of air raids alarms, machine guns, explosions of mines and shells. They are the children of war.

The educational and psychological camp Gen.Camp works for children who suffered from Russia’s war crimes in Ukraine, who became orphans or semi-orphans. Ukrainian psychologists help children overcome the terrible experience of war, teach them to live in a new reality and grow up as healthy and strong Ukrainians. During two shifts of the camp, 62 children from hot spots aged 6 to 12 underwent free rehabilitation.

‘Bukvy’ had an interview with the founder of the NGO Gen Ukrainian Oksana Lebedeva and the main psychologist of the project Oksana Shlionska.

What values does your cam promote? Do you have your own creed that you adhere to when working with children?

Oksana Lebedeva: Our camp was created to provide children with a safe environment for such a psychological process as grieving. Our task is to reduce the consequences of war traumatic events for children who are the most vulnerable part of the population. All children undergoing rehabilitation in the camp had a difficult traumatic experience: there are children who lost a mother or a father, or both parents. Some of them lost brothers and sisters.

The main goal and value of such a safe environment is that a child can be whatever he/she wants to be. A child can be aggressive or choose any other strategy for suffering. This may be the behavior that parents cannot control. A child can talk a lot, or not talk at all, play, have fun, or constantly rest. That is, the main value is to give a child the opportunity to be in any condition, in which he/she is now, and to teach little by little, to show the advantages of more cheerful and effective strategies.

As for the credo, I really like the following phrase, ‘when a child is suffering, one must close one’s mouth and open one’s arms’. This is the credo of our organization, especially when we intensively work offline. We try to understand, hear, find the key to the heart of each child, because psychotherapy is the art of interpersonal relations, establishing this connection is possible only by choosing an individual path to each child.

Trust is the basis of feeling safe. Please, share what methods, words, or actions you use to establish a line of trust with each individual child.

Oksana Lebedeva: Trust does not come by itself, which is why our program lasts 21 therapeutic days, because we need time to open up, do the work and close all the processes. Children feel artificial behavior, so you can make friends with them only honestly. Each child chooses different people to establish a connection, and often it is not a psychologist. That is, the child attends group and individual classes, but chooses, for example, a tutor or our doctor for private conversations. Actually, it is not important who exactly falls into the zone of trust, because at the end of the day, my team and I conduct work sessions where we analyze each child. Therefore, any person who has earned the child’s trust contributes to the work on his/her mental health.

Therefore, there are no special methods. We spend a lot of time with children, together with them we suffer, have fun, play sports, dance, play, draw, and this process of establishing trust is organic. Someone needs more time, and someone will tell everything right on the bus on the way to the camp. Every child is unique.

What traits are common to all the children who get to the camp and what emotions do you have to work with?

Oksana Lebedeva: All children are different, they have in common grief and war and they constantly talk about it. That is, war is an absolute phenomenon for them. It is present in everything they discuss among themselves, in games. This unites them. Undoubtedly, the emotion that all children experience is fear. However, the fears are different: for the lives of loved ones, for the country, for the home, for friends, for relatives, for their pets, the fear that the Russian military will return – this is what the children who were in the occupation are afraid of, the fear that someone else from relatives will die.

We have a separate section in the program; separate days are dedicated to working with these fears. For example, the ‘Fear Fair’ therapy, when children sell their fears and keep a little for themselves. They sell big fears and they keep smaller ones for themselves. There is a whole program built on working through this emotion. It always gives its results.

Do they feel fear for their own lives?

Oksana Lebedeva: Yes, of course they feel fear for their own lives. For a child, the loss of parents is a vital fear, because they associate their existence with these people, and this is normal for the age of 7-11. Teenagers have a slightly different focus, and they fear even more for their lives. Most of them felt a threat to their own lives, were in the midst of military operations, saw horrors with their own eyes. Almost all children in our camp have seen military operations and in one way or another experienced fear for their lives.

Do children often talk about war? Do they express a desire to return to their native places?

Oksana Lebedeva: Our camp participants are children who are mostly in their native lands, that is, they are not refugees. They either are internally displaced persons or simply continue to live where they lived before the death of their parents. The first two shifts of the camp were held in Spain, and the children, being abroad, often say that they want to live at home. Especially Mariupol children. They constantly talk about their city as something very close to them; they remember what life was like before the war.

Children often talk about war; it is an absolute axiom of their life. They play the war, talk about it, and sing military songs. This is what we see after several shifts and work with hundreds of children.

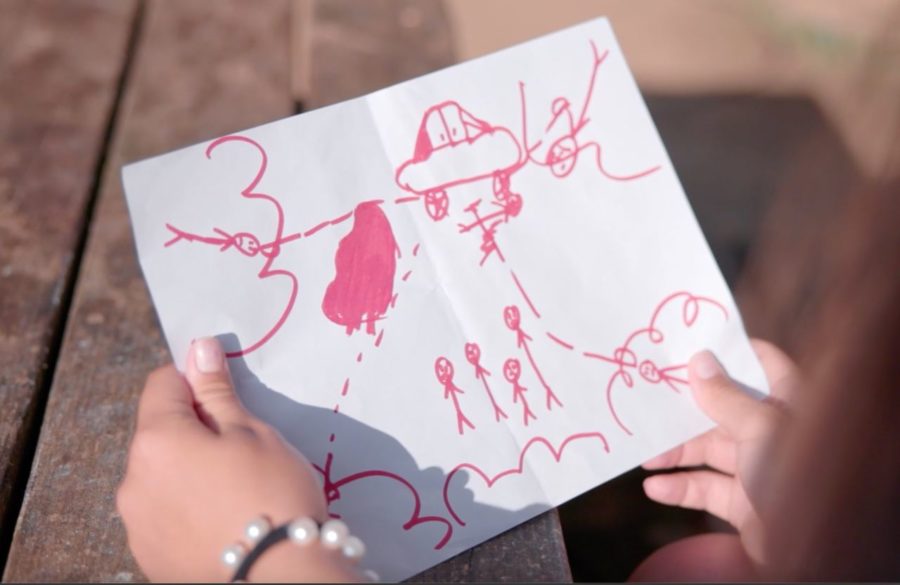

Can you single out a common message of children’s creativity, in particular of drawings?

Oksana Lebedeva: Unfortunately, this is a military theme, all the time. Children sculpt, draw, and carve military scenes. We were shocked when the second shift of children arrived and we gave them art therapy materials, all 32 children chose the same theme. There were no flowers. It was a war. Girls modeled dead invaders, boys – torn bodies, painted a lot on the theme of victory, i.e. yellow and blue flags, inscriptions ‘victory’, favorite city, house. When we come to therapy, where one needs to draw own past, present and future, they always draw a family. This is common to the children, because it is a painful topic. They have lost the loved ones, so they usually draw those who are left behind and add someone from heaven.

Do they fancy t their own future?

Oksana Lebedeva: There is the ‘Triptych’ tool, which is the element of our ‘Protected by Love’ program. There, children draw their past, present and future. Talking about the future means coming out of trauma. What do injuries do? Injuries drive a person into the ‘here’ and ‘now’. That is, the past is impossible, there is a lot of pain, and the future is impossible, because it is simply impossible. It is extremely important for us to take them into the future, see, fantasize and plan. Plan the next day, plan the next week, plan the holidays. This is a necessary component of the psychological rehabilitation of a child and an adult as well.

What stories were the most challenging experiences during the camp and impressed you the most?

Oksana Lebedeva: All the stories are very touching, perhaps the ones are even more memorable when you understand that the work with these children does not end and you have to continue.

This is the story of Andrii from Brovary, whose mother, father and uncle died in the car in which they tried to evacuate, but come across a column of invaders.

This is an extremely difficult case when a child can talk about everything, absolutely everything, but feels nothing. That is, the stress is so strong that he experiences emotional anesthesia, which is very prolonged, because he does not distinguish between his feelings, does not quite understand where the reality is and where it is not, where he is happy and where he is sad. He does not distinguish between his conditions. This child will continue to work with a psychologist, because he has all the signs of severe grief.

I remember the first girl in the camp – Maya from Kharkiv. Her father sent the family away, but he himself remained to volunteer and was shot in the car while taking medicines to Saltivka Kharkiv district. The family learned about the death from Telegram Messenger. The child underwent rehabilitation in the first camp. She has such a peculiarity – she corresponds with her father. This is actually not exceptional because many children do this, but she expresses it in an extremely interesting way. That is, it becomes easier for her when she corresponds with him. Very often, she sends to him photos, shows different things and consults with him. This story was very memorable. However, of course, every tragedy of a small child is exceptional.

For children who have lost their parents, home, peaceful childhood, what can be a challenge in the future?

Oksana Shlionska: Loss and its traumatic consequences always affect the future. The strongest psychological injuries, not to mention physical, children and adults receive precisely during the war. Because at this time, the picture of the world created by us is literally collapsing. Only the person him/herself is able to rethink what happened, to understand the misfortunes that befell him/her as a part of life, and not as a punishment for something, and to find realistic ways to overcome difficult circumstances. Such activity is possible for adults, but children need our help.

If children do not receive the help and support of adults, then the most dramatic challenge in the future may be the loss of basic trust in the world. This leads to a chain of problems: the inability to believe in one’s own strength, to feel the taste of a full life (we do not live, but survive), mistrust of people, the division of people into the ‘own’ (those who survived the war) and others (those who left), search for enemies. With this chain of problems, it is very difficult to build the future.

Viktor Frankl, who is now quoted a lot, said that everything could be taken away from a person except the sense of inner freedom, which allows one to form own attitude to suffering. It is about adults. We can really find our own meaning even in such terrible times, become stronger, more resilient.

It is more difficult for children, because they are still dependent on an adult and the feeling of inner freedom is just forming. Therefore, if an adult is nearby who will help, teach how to create meaning every day, teach how to see what a child can do for other people, for life – we will see the post-traumatic growth of such a child. If there is an adult nearby who cherishes suffering, disables the child, gives, then the future will be difficult: violation of adaptive capabilities, rejection of him/herself and others, emotional discomfort, escapism, learned helplessness.

Are there effects of war on children’s psyches that can never be overcome?

Oksana Shlionska: Recently, a large number of studies have been conducted around the world on the condition of children who were in war zones. Most authors agree that the consequences of psychological trauma are anxiety disorders, aggression, depressive disorders, pathological mourning, and the inability to build a future. However, it is also emphasized that children are very resilient and their ability to adjust their lives after the end of the conflict depends on the resilience of close adults, on the socio-economic situation, on help, on meeting the child’s basic needs.

Therefore, if we want our children to overcome the consequences of war, we must nurture our resilience, our ability to recover, to be useful and not to tire of what we have to endure. Children learn not from moral speeches, but from our example. The inevitable consequence will be the memory of the lost past, of the family that is not there, of the house that was destroyed. However, this memory should not prevent us from building the future. For this, the child needs help, perhaps of a psychologist.

What should a child/adolescent who has experienced a severe traumatic event remember?

Oksana Shlionska: A difficult question. Perhaps there is no universal answer. However, resilience and the ability to recover are important. That is what helps. In order to be sustainable, we must remember values. Not material, because you cannot hold on to them during the war, it increases the feeling of loss. We mean what we would like to be at our best. When you remember the values, for example, to be involved in the victory, you can form goals and then act. My grandfather, who went through the war, used to say to me when I was still small, when I was sad, ‘What good things can you do? Do that and the sadness will go away…’

If we are grieving a loss, we should remember that grieving is normal. We have to mourn what is dear to us. This cannot be skipped, this path must be passed, but it is worth turning to people, relying on friendly support, not being alone.

One should believe. Because losing faith in oneself, in people, in the army, in friends, in victory is scary! Disappointment can be the result of a traumatic event, especially when this event is extended over time. In addition, it is also worth remembering about changes. For example, the idea that ‘the darkest night is always before the dawn’ helps me a lot.

To get help and become a participant of the camp, one needs to fill out the form on the website https://genukrainian.com.ua and go through an interview with the project coordinator.

Gen Camp project on social networks:

Creative director of ROA Patrick Stengbye talking about the shoes he chooses for running, what the brand will surprise us with in 2024 and President Zelensky’s style

Creative director of ROA Patrick Stengbye talking about the shoes he chooses for running, what the brand will surprise us with in 2024 and President Zelensky’s style