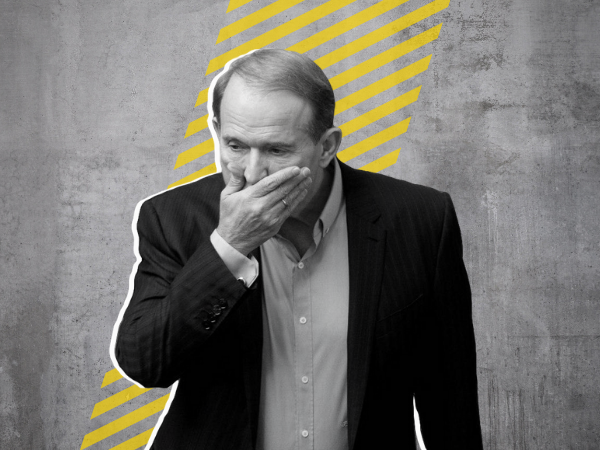

Zelensky’s variety show of politics and crime does not produce the desired effect anymore, faces declining rates of public approval, and sees Medvedchuk enjoying political gains, and yet ‘the show must go on’.

Zelensky’s variety show of politics and crime does not produce the desired effect anymore, faces declining rates of public approval, and sees Medvedchuk enjoying political gains, and yet ‘the show must go on’.

On all accounts, the story of ‘notice of suspicion’ issued for Medvedchuk leaves an impression of some amateurish spectacle. In her press briefing, the chief prosecutor Iryna Venediktova announced that Viktor Medvedchuk and Taras Kozak were issued an official ‘suspicion’ on charges of high treason and attempted ‘looting of natural resources’ in Crimea.

In the first place, Mrs. Venediktova, when citing the charges, misquoted the article 348 of Ukraine’s Criminal Code that assumes accountability ‘for attempted murder of a law-enforcement officer [..] or a serviceman’, and this , obviously, has nothing to do with art.439 citing ‘looting the natural resources in the occupied territories’.

The issue of tangibles in the event of armed conflict is regulated by two international laws. The 1954 Hague Convention for Protection of Cultural Property covers ‘immovable and movable cultural heritage’, and there is no mention of such thing in the investigation on Medvedchuk. The Geneva Convention seeks to protect ‘those who at a given moment and in any manner whatsoever, find themselves, in case of a conflict or occupation, in the hands of persons a Party to the conflict or Occupying Power of which they are not nationals’. This convention cites ‘destruction of property’ but has no mention of ‘appropriation’ or ‘transfer of rights to third parties’ which are the things Medvedchuk is accused of.

The wording makes a great difference for all law professionals except for Ukraine’s Prosecutor General office. In their charges against Medvedchuk, they talk about looting of ‘national assets’ while the article 438 of Criminal Code they refer to cites ‘national valuables’. The latter term has no clear legal definition and can hardly be regarded as the equivalent for ‘national assets’. The term ‘looting of national valuables’ by any means can not translate into ‘alienation’ claim making the charge against Medvedchuk inapplicable in his criminal investigation unless they will have Criminal Code amended.

The decision to base the charges against Medvedchuk on the article 438 of Criminal Code looks strange in the light of the ongoing investigation on his ‘sponsorship of terrorism’. The investigation is still proceeding and lacks sufficient evidence, said Ivan Bakanov in the press briefing, in stark contrast to the ‘looting’ story where the state prosecutors claimed they were ‘fully confident’ of the proof validating their charges.

Notably, National Security and Defence Council earlier used ‘sponsorhsip of terrorism’ allegations to impose sanctions on Medvedchuk TV channels and entities. The move got a strong public reaction but its legal aspects remain questionable.

The charges of high treason pressed against Medvedchuk and Kozak show promise but you can hardly be ‘fully confident’ they will work in court.

The investigation failed to explain how and where Viktor Medvedhuk obtained the classified information on the secret Ukrainian military unit, which he later allegedly passed to Russians. Unauthorized disclosure of state secrets is a serious crime under Criminal Code (art. 328, 329, 422), and the persons who had provided Medvedchuk with this classified information must also be brought to justice.

The SBU and Prosecutor General’s office are tight-lipped on the sources that handed this information over to Medvedchuk. They chose to state that the classified information was sent to Taras Kozak who assumingly passed it to Russian intelligence agencies.

The second case appears to lack substance and have been calculated to garner media attention and reaction of voters. It looks undeveloped in view of how detailed and revealing was the account of the first case on ‘looting natural resources’ that boasted transcripts of taped calls and copies of official documents.

The third case found Medvedchuk involved in the organization that allegedly recruited Ukrainians studying or working in Russia for propaganda campaigns against Ukraine. It is an open secret that Russia exercises leverage over media campaigns and political processes in Ukraine under the disguise of different public projects and organizations.

Citing the article 111 of Criminal Code, the SBU investigation found Medvedchuk conspiring to ‘influence the political situation in Ukraine’. The investigators though failed to clarify what kind of ‘damage’ his activities inflicted on the state of Ukraine, which is what the art.111 commands for it to be called a crime.

That same logic can be applied to Volodymyr Zelensky for his orders commanding withdrawal of the Ukrainian troops in Donbas, which can be equally treated as high treason.

It may sound as judicial sophistries but this is exactly what Volodymyr Zelensky and his team are trying to use in their stand-off with Medvedchyk. It can be okay for a media person or a politician but will hardly work well for prosecutors in court. Medvedchuk’s defence will surely pick on all these flawed and weak points.

Can investigations produce substantial evidence to press charges against Medvedchuk? Probably so. Can he be indicted on the allegations provided by Venediktova and Bakanov? Probably not.

The law-enforcement officers who came on a search warrant to the residence of Medvedchuk looked like a group of sheepish employees showing up at managers’ office, cap in hand, to ask for a pay rise. Iryna Venediktova was visibly caught unprepared for swift arrival of Medvedchuk to her office coming up with her routine mantra of ‘ongoing investigation’ and ‘lack of evidence’. All this comes as a clear sign that the Prosecutor General’s office is aware that t they are on the thing ice with a ‘notice of suspicion’ for Medvedchuk. The political motives yet again outweighed other considerations.

Creative director of ROA Patrick Stengbye talking about the shoes he chooses for running, what the brand will surprise us with in 2024 and President Zelensky’s style

Creative director of ROA Patrick Stengbye talking about the shoes he chooses for running, what the brand will surprise us with in 2024 and President Zelensky’s style